Dorasar was what the ancient Greeks would have called an oikist, the founding leader who held near-absolute authority during the establishment phase, only for the colony to transition to an oligarchic system within a generation or so.

In the real world, Cyrene and Tarentum are good examples of this dynamic, and good models for understanding Dorasar and New Pavis. For example Cyrene was founded in 631 BC by the oikist Battus I who became the first king, establishing the Battiad dynasty. However, internal conflicts and new settlers led to reforms under Battus III (c. 550 BC), which curtailed royal power, transferring most authority to oligarchic institutions while retaining the king mainly for religious roles. The monarchy fully ended around 440 BC, turning Cyrene into a republic. Tarentum was founded in 706 BCE by an early Basileus but it became an aristocratic republic within one or two generations.

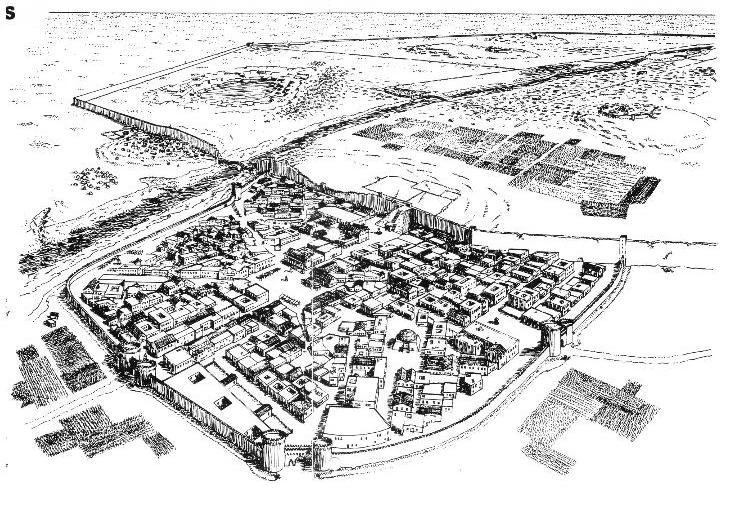

In Glorantha, Dorasar served as the oikist equivalent, a member of the Sartar dynasty acknowledged by the colonists because of his status and deeds. He wielded extensive powers: selecting the site, distributing land, organizing religious cults, and laying out the urban plan. Upon his death, power transitioned smoothly to a city council composed of leading kinship groups (e.g., heirs of Dorasar’s companions like Garhound, Varthanis, Indagos, and Ingilli), guilds, and temple representatives (especially Pavis, Orlanth, and Issaries cults). No hereditary monarchy was established by his children; instead, the city emphasized collective rule by elites, much like the oligarchic shifts in Greek colonies.

A big part of why this happened this way was environmental. New Pavis was in a relatively secure river valley niche, with alliances buffering nomad threats, so a permanent war-leader “king” (like the Princes of Sartar) wasn’t deemed necessary. In a more exposed or dangerous setting, his dynasty might have persisted longer—but it was seen as unnecessary by the leading kinship groups, guilds, and temples.

These sort of arrangements have a long tradition within Orlanthi culture. Nobody would see this as a particularly big break with Sartar – the shift from the strong, personal leadership of a founder (or short-lived monarchic phase) to a self-governing oligarchy would not have been seen as particularly radical by the Orlanthi. The establishment of a self-governing polis through the temporary strong leadership of an oikist-like figure (like Prince Sartar himself), followed by a transition to city council rule—could easily coexist with the overarching authority of a more powerful Prince.

In the real world, this was the standard arrangement across much of the Hellenistic world (c. 323–31 BCE). The great successor kingdoms (Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleucid Asia, Antigonid Macedonia) were territorial monarchies ruled by absolute kings, yet they incorporated hundreds of Greek-style poleis that retained significant internal autonomy, including oligarchic governance. Similarly they easily coexist with the presence of a Prince or King, be it Sartar, Tarkalor, or Argrath.

![]()

![]()

And so when Argrath liberates New Pavis, he establishes himself as the rex and this fits within the accepted parameters. Heck, it’s the Orlanthi system working exactly as designed—reverting to strong personal leadership under a proven hero when survival demands it. Once the immediate crises subside (in theory), power could again diffuse, but Argrath’s larger ambitions keep him in the rex role.

That Dorasar founded New Pavis outside of Old Pavis also has plenty of historical antecedents. Founding a new settlement adjacent to (or incorporating) the ruins of a much older, legendary, or ruined city was a recurring motif in both the classical Greek and Hellenistic worlds. It carried prestige—connecting the new foundation to ancient glory, heroic myths, or divine favor—while pragmatically exploiting an existing sacred or strategic site. Antioch, Seleucia on the Tigris, Smyrna, Ephesus, Priene, Magnesia-on-the-Maeander, are all good examples of this.

Even the role of the Pavis cult has plenty of real world parallels—transferring or continuing old city cults into the new/refounded settlement was a common and deliberate practice in Hellenistic (and some classical) refoundings. It lent the new city legitimacy, prestige, and a sense of continuity with an ancient, prestigious past. Just like New Pavis with the Pavis cult.

As an aside, Orlanthi culture is built for exactly this kind of rapid, pragmatic shift from dispersed/collective governance to strong personal leadership (and potentially back again) without it feeling like a revolution, betrayal of tradition, or even a particularly radical change. The same system that lets power diffuse into oligarchic councils and democratic assemblies when things are calm also lets it concentrate into near-absolutism when a dominant personality rides a wave of crisis and success. The Orlanthi don’t see this as hypocrisy, they just view it as being similar to their storm god himself.

Another ramification of this is that New Pavis (or any other Orlanthi entity) doesn’t have a proper, impersonal bureaucracy. Administration is personal, amateur, and tied to elite status rather than a permanent professional civil service with hierarchical offices, standardized procedures, and continuity independent of rulers. Scribes record land grants, tribute tallies, or judgments, but those decisions flow from the leader’s (or council’s) personal will and relationships, not from impersonal office procedures. Orlanthi “administration” is always ad-hoc and tied to personal loyalty: it serves the man, not the office. When the rex dies or falls, or the council changes makeup the staff disperses or realigns with the new leadership — there’s no continuity of a neutral civil service. The rule always stays fundamentally personal, rather than embedded in enduring, rationalized institutions.